Hayao Miyazaki is known in film circles as the Walt Disney of Japan. As a writer and director, he has brought us such classics as My Neighbor Totoro and Princess Mononoke. In each of these masterpieces, he hand-draws tens of thousands of individual frames. His films are recognized for their grand scope and unforgettable characters. It always amazes me to think that a Miyazaki film is as epic and original as Star Wars, only to be dumbfounded by the fact that each unique Miyazaki film is equally magnificent. He may not be as prolific as a Woody Allen or an Alfred Hitchcock (though he certainly deserves to be compared to such luminaries) but every Miyazaki film is a classic.

I was happy to learn that the readers of Tor.com had recognized Spirited Away as one of the best films of the decade. Many fans and critics agree it is his best film. Spirited Away won the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival, the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature Film, and it was the first film in history to make more than $200 million at the box office before opening in North America. The film has a special place in my heart. I first saw it in theaters during the original US release. Although I had previously watched Kiki’s Delivery Service and Princess Mononoke, nothing could compare to the experience of watching a Miyazaki film on the big screen. I remember being absolutely floored by the intricately crafted imagery and the lasting impact of the story. Every time you watch Spirited Away, you discover something new. I’d like to talk about some of these discoveries below.

Spirited Away is the story of Chihiro, a sullen and whiny girl (in other words, an average ten-year-old), whose parents are moving her to the country and away from her old friends and school. When her father takes a wrong turn and the family ends up lost in the woods, the ordinary girl finds herself in an extraordinary world. The family discovers a tunnel that leads to fields of endless wavy grass. Notice how the wind seems to pull Chihiro towards the tunnel. Once she enters this “cave,” she has passed the magical threshold. This imagery is familiar to much fantasy literature, including A Princess of Mars, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Alice in Wonderland, to which Spirited Away is often compared.

Miyazaki’s use of light and shadow in these early scenes is amazing. He captures the fuzzy glow of a sunbeam filtered through a stain-glass window and dust motes floating in the air. The film uses a slow build of walking across landscapes. The deliberate pace puts the audience in a contemplative mood. The film is not plotted like most western animated films. Character movement, especially at the beginning, is realistic. Definitely not the anime norm.

The family discovers an abandoned theme park beyond the grassy fields. Chihiro feels uneasy and does not want to explore the park, but her parents follow their noses to a great feast, steaming, delicious, and abandoned, at one of the fair stalls. They start gorging at once, but Chihiro refuses to eat.

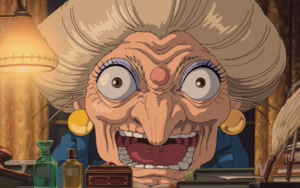

This scene and others are examples of how Spirited Away is laden with symbols and other elements of fairy tales and folk lore. Miyazaki borrows from many cultures, including cursed food and objects of germanic folklore, the western image of the princess and the dragon, and bath house owner Yubaba is a dead ringer for the Russian witch Baba Yaga. The majority of Miyazaki’s inspiration, however, comes from the Japanese Shinto and its eight million gods who embody the mountains, trees, and rivers of the natural world. These gods, or kami, were translated to spirits in the Disney-produced English dub of the film to avoid alarming puritanical American audiences.

Chihiro meets a boy Haku, who urges her to leave the fun park before dark, but when Chihiro returns to her parents, all that food they ate has turned them into giant pigs. Chihiro runs, but night falls, and the grassy plains have turned into a lake.

Haku works at a bath house for the gods, a place where the spirits of the natural world can replenish themselves and rejuvenate. Themes of growth and renewal are prominent in Spirited Away, and Shinto as well. Over the course of the film, Chihiro must perform great deeds in order to be purified.

Haku explains that Chihiro must get a job at the bath house in order to stay in the spirit world. Her eventual plan is to find her parents and escape, but for the moment Chihiro agrees to meet this challenge. Reflecting upon the way Chihiro fumbles through this opening adventure, being frightened by a staircase and crying in a fetal position while hiding under a bush, we see just how much Chihiro grows over the course of her adventures.

In a Miyazaki film, there is never only one thing moving on screen at a time. For example, when Chihiro meets Kamaji in the boiler room, Kamaji’s whole body is moving, the fires are burning, smoke is billowing out of the boiler, the soot workers are crawling along the floor, and Chihiro is approaching the scene tentatively. When you consider that these frames were hand-drawn, the skill of Miyazaki and his production team is apparent.

Eventually, Chihiro gets a job working in the bath house. Much of the remainder of the film follows Chihiro and her adventures in the bath house of the spirits, performing great deeds while growing stronger and more confident. In the bath house sequences it is interesting to see everyone, especially Yubaba, hard at work. She is wicked but competent, adding depth to her character. Although she looks very different from Lady Eboshi in Princess Mononoke, they have much in common. Both are ruthless, both are superb leaders and display incredible skills (Yubaba at magic and Eboshi at swordplay), both are humanized by their compassion towards one entity (Yubaba for her baby, Eboshi for her lepers).

What distinguishes Miyazaki from other animators is the way he slips little details into the action of his scenes. Kamaji’s dirty food bowl sits on his desk, and when he reaches for a high drawer, a little bit of grass falls out of his hand. When Chihiro’s dad runs towards the camera, there’s a flash of the zipper on his jeans. As Chihiro runs across the hardwood floors, we see dirt on her feet. At the table in Zeniba’s house, before she gives Chihiro her magical hair tie, the mouse and bird-fly sneak on screen, nibble cookies, grab a few more for the road, and scurry off-screen. No one in the scene acknowledges them. There are long, meditative pauses as Chihiro sits up in bed, discovers an empty room, or gazes out over the endless ocean.

Once in an interview, film critic Roger Ebert asked Miyazaki about this element:

“We have a word for that in Japanese,” [Miyazaki] said. “It’s called ma. Emptiness. It’s there intentionally.”

Is that like the “pillow words” that separate phrases in Japanese poetry?

“I don’t think it’s like the pillow word.” [Miyazaki] clapped his hands three or four times. “The time in between my clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it’s just business, But if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension. If you just have constant tension at 80 degrees all the time you just get numb.”

Although not nearly so heavy-handed as Princess Mononoke, the writer-director’s eco-friendly message is still at the core of Spirited Away. One spirit is the embodiment of the river so polluted that he becomes a stink spirit (more like a poop spirit, given the appearance), and Haku, who can’t find his way home because his river was drained and paved into apartments.

The climax of the second act features parallel action. While downstairs No Face gobbles food and torments the bath house employees, Chihiro races to the top of the bath house to find the injured dragon (really Haku in dragon form). These two plots collide when Chihiro gets sidetracked by the B-plot. Hilariously, she refuses to get distracted for too long. This escalates plot B, when No Face starts gobbling the workers.

Chihiro’s journey to the top of the bath house mirrors her journey to the boiler room at the bottom of the bath house earlier. But look how she handles the pipe and ladder as she races to to rescue Haku. Compare this to the wooden stairs at the beginning. She has become a full-fledged hero now, not a victim. She saves her man.

I could go on forever. Every frame of Spirited Away is a work of art, and the themes, mythos, and symbols of the story have deep resonance. Miyazaki is such a good director he rarely gets credit for his writing, which is always brilliant (although sometimes jumbled by Americanized translations). The English versions have great voice talent, and are worth watching for their immersive quality if you don’t speak Japanese, but watch them in Japanese too. The little changes go a long way.

Chihiro is a gutsy female protagonist. She performs three tests. One is physical (the stink spirit), one mental (she kneels and talks to No Face, figures out that he needs to leave the bath house), and one emotional. Love is what allows her to save Haku.

Spirited Away deals with the importance of memory, of both preserving the past and remembering who you are. I always have a strong sense memory when I watch Chihiro pull the bicycle out of the stink spirit. The amount of sludge and garbage pulled out of the spirit’s body defies physics, but it reminds me of a time when I was a Tiger Cub in northern Massachusetts. My brother and I volunteered to help an older boy with his Eagle Scout community service project, which consisted of cleaning up a patch of the Shawsheen River, which has one of those beautiful old native american names, yet suffered more than a century of toxic dumping from the textile mills and other factories along the Merrimack and its tributaries. Under the surface of the brown-green water, we found, among other things, car tires, televisions, shopping carts, hypodermic needles, undergarments, and a two-door refrigerator, all embedded in the sludge of the river bottom. “I watched them drag the fridge to shore” is a sentence one should never hope to utter, but I can imagine Miyazaki has made similar statements in his life. The detail in his films portrays a keen understanding of the beautiful minutiae of the world. In the special features on the DVD of Spirited Away, Miyazaki provides his staff with places to look for inspiration. The heavy thunk of a snake falling from a tree, the way a woman forces open a dog’s mouth, these are not just images, but motions, which find their way into the animation of Spirited Away.

In the end, Chihiro proves herself, saves her parents, and returns to the real world. She gazes back into the dark tunnel she entered at the start of the film, perhaps wondering if her great deeds were all a dream. She turns, to run to her family, and there is a flash of her magic hair tie, as if the little charm is telling Chihiro, and us, to remember.

Matt London is an author and filmmaker who lives in New York City. He is a graduate of the Clarion Writer’s Workshop, as well as a columnist for Tor.com, Lightspeed, Fantasy Magazine, and Realms of Fantasy. His fiction is out right this second in the anthology The Living Dead 2. Follow him on Twitter.

I think Spirited Away transcends Anime and is among one of the best films ever made. I have rarely been able to get friends and family to watch Anime with me, but this film never fails to open peoples eyes to the wonderful world of Anime.

Great post. I always enjoyed the moments of “ma” without ever acknowledging them consciously, but now that I know what to call them, I can say that they are maybe the most beautiful and defining moments of the movie for me.

In each of these masterpieces, he hand-draws tens of thousands of individual frames.

Of course he does not. He has a staff of animators and key animators, like any other director. He does do the concept sketches, much of the storyboarding, and even some wonderful watercolors as he “writes.” He’s also known for careful editing of the cels of the key animators to improve the timing of the frames. Most of his films have an associated The Art of ____ title (Full disclosure, I edited The Art of Ponyo) for people interested in in-depth looks at the animation from the concept sketches on to the finished product. They also often include pretty interesting and occasionally technical interviews with key animators, color designers, the art directors, etc.

I’ve seen this movie once and, honestly, it took me a while to decide if I liked it or not. Its pace and story-telling style weren’t what I was used to. But it was beautiful so I stuck through it. Then it stuck in my head for days. I spent that time trying to figure out what it all meant. Here’s what I came up with:

Chihiro meets a lot of characters that have shady pasts. I started to consider them all bad guys. She decides to trust them and her trust seems to turn them all into good guys. A little trust and a little benefit-of-the-doubt goes a long way in this movie.

Whether or not that is what Miyazaki was trying to say with this movie doesn’t matter to me. It’s what I saw and, as a result, I had to conclude that I loved this one.

I love this movie. The bath house and resort village feel like utterly real places.

It gets a little liesurely toward the end (trolley voyage), perhaps deliberately, as a kind of cool-down cycle after the intense stuff (filth monster, hungry ghost, paper doll attack). But still, a rocking good story.

I’m considering getting the Blu-Ray version to better soak in the sheer loveliness of it. I’ll send the DVD to my nieces; I essentially made my sister show it to them. Quite an eye-opener; they’ve seen almost all of Miyazaki’s films by now.

This is one of the most time dangerous movies I own. There is not one moment of this movie when I can stop watching and fold some laundry or put away some dishes. It is a movie that commands my every attention.

Sometimes I think, “I just want to watch this one scene…” and I will watch the entire movie. Honestly I cannot even hear the music without starting the movie in my mind and getting distracted as it plays through.

I so very rarely belive that there is such a thing as a perfect movie but in the world of Miyazaki it is much more difficult to belive that a movie cannot be perfect.

Also, and it may sound pretentious, I honestly believe that it is better to watch all of his movies in Japanese and just read the subtitles.

In the case of these films I would rather expand my understanding of a different culture to appreciate the effort that goes into making such excellent films than have the films adapted to the culture I am currently familiar with.

Spirited Away is truly one of the best films in any format from any time. It is possible that there may be a person in the world who may not like this movie but I could not understand that person. :)

I first saw Spirited Away when I was six years old at a friend’s house with my siblings. I liked the movie at first, but I didn’t really get what it was about. A few years later, I rewatched it and instantly fell in love.

Everything described in Matt London’s article is why I love this movie. Especially the mouse and bird/fly. They’re hilarious. But anyway, this movie teaches large lessons about growth and determination. With determination, almost anything can be done, whether it’s winning a race or saving your parents who have turned into pigs by helping in a bathhouse for spirits, saving the spirit of a nonexistent river, standing up to an old lady who can fly, and making many friends along the way.

Thank you, Miyazaki.

I only refer to Miyazaki’s stuff as “anime” to those who do NOT know who he is and only out of lazy convenience. His films are works of art on par with anything else you can come up with.

I’ve always wondered why Chihiro gets described as whiny or sullen. Because she’s tired and headachey after a long car drive? Because she protests her parents’ hoggish commandeering of other people’s food? Because she has the gall to be upset when her parents are horrifically transformed and she’s abandoned in a world of strangers? Because she in general shows opinion and forethought of her own while the adults around her insist she perform dangerous or stupid maneuvers?

Seriously, I know this is the official description, and part of the movie’s arc is Chihiro becoming more than she was, but I’ve never seen anything in her behavior that invited any of the negative descriptors often used on her. Someone fill me in, what I am missing here?

Spirited Away is the best kind of fairy tale: the kind that mixes the wonder of childhood with the horror of growing up. The kind that draws you in with small lies and leaves you with giant truths.

I never got it.

I just don’t see what everyone else loves about this film. That might be just me because I’m not a great fan of Miyazaki in general (love Princess Mononoke and The Castle of Cagliostro but I don’t love his other works).

Maybe I just need to rewatch them in the original Japanese instead of the dub.